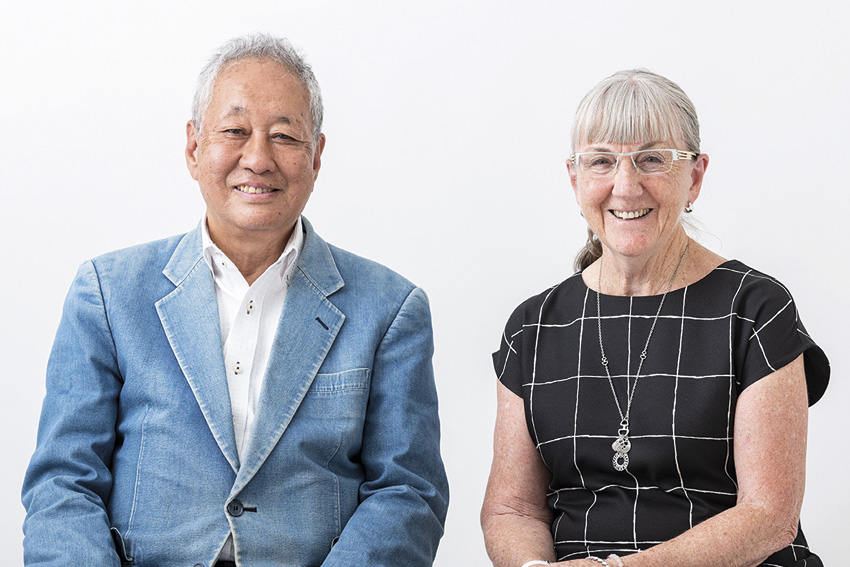

Sangi is a trailblazer in dental care, having harnessed the key component of teeth, hydroxyapatite, to develop ground-breaking, enamel-restorative toothpastes. Founded in 1974 by Chairman Shuji Sakuma, Tokyo-based Sangi began life as a trading company which, according to president Roslyn Hayman, “sold all kinds of things, such as wine, Australian surfboards, even French lingerie”. However, a game-changing moment came when the firm acquired a patent for remineralizing teeth from the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). We sat down with Shuji and Roslyn to learn more about the company, its history and the wonderful benefits and applications of hydroxyapatite.

Your famous Medical Hydroxyapatite, also known as nano , is a space-inspired ingredient developed originally by Sangi and officially approved as an anti-caries agent. Moreover, you launched APADENT, the world’s first toothpaste to contain hydroxyapatite, as early as 1980, and went on to develop a wide range of products using it. Could you tell us more about the story of your ingredient, and which are your best-selling products now?

Roslyn: Shuji started the business as a trading company in the 1970s, just before we were married, selling all kinds of things, such as wine, Australian surfboards, even French lingerie. One item was intellectual property, as he was asked by some Japanese dentists to acquire a patent from the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) for a precursor of hydroxyapatite, the key component of teeth. NASA’s idea was to use this precursor as a poultice for the teeth, to create new hydroxyapatite and restore density to tooth enamel, particularly for astronauts who are prone to suffer mineral loss in a zero-gravity environment.

NASA’s suggestion was to use this precursor (brushite) to recreate new hydroxyapatite on the teeth. But Sangi went one step further. If hydroxyapatite is the same substance as tooth enamel, why not use it as an ingredient in toothpaste, to remineralize and protect people’s teeth during everyday brushing? That was Sangi’s original idea.

Only recently, a publication in Europe announced that hydroxyapatite toothpastes were first developed by NASA and that Sangi simply purchased the rights and started making the product. That is totally wrong, and it needs to be corrected. We were quite surprised, as the article was by a company we know quite well and which participated in the first International Symposium on Nano-hydroxyapatite in Oral Care, which Sangi sponsored at the International Association of Dental Research (IADR) meeting in London in 2018. One of their research staff acted as co-chair.

Hydroxyapatite toothpastes first began appearing in Europe after nano-hydroxyapatite was independently “discovered” by German chemical companies BASF and Henkel at the beginning of this century. Henkel came to us, and we worked together for a time and had a good relationship with them. For some reason they later dropped out of the market, and BASF didn’t go ahead, apparently because of nano-safety concerns. They were handling the ingredient, rather than the finished product. Since then, numerous products with hydroxyapatite have appeared, some claiming to be “the world’s first,” which we find quite irritating. Probably because most of our early research was published in Japanese, it wasn’t recognized until later when we began publishing in English. But these days our role as pioneer is generally recognized worldwide.

There are quite a lot of toothpastes now, for example products containing bioglass, that put calcium and phosphorous or other ingredients together to create hydroxyapatite in the mouth. That was what the NASA patent proposed. But when Shuji acquired the patent and the Japanese team started handling it, they found it wouldn’t work, so they came and complained to him. In response, he said “If you want to create hydroxyapatite on the teeth, then why not use hydroxyapatite itself, and put it in toothpaste?” After all, we brush our teeth three times a day, and the phenomenon called remineralisation is a totally natural one: our saliva is constantly providing minerals to the teeth without us realising.

By 2050 we’re expected to have less than a hundred million people in Japan, and one third of them will be over the age of sixty-five. When we look at the world population, other countries are not very far behind Japan, they’re also ageing, and dental prosthesis has increased worldwide. As we get older, we produce less saliva but nano has the ability to remineralise teeth. Could you talk about the benefits of your products for the older generation?

Sakuma: We’re seeing this initiative led by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) in the dentistry area. It’s called the 8020 (Eighty-Twenty) campaign, meaning that by the time people are eighty years old, we want them to have kept at least twenty healthy teeth of their own. This is so they can depend on themselves, eat and chew well, and lead a healthy life. We’re seeing this initiative gaining success here in Japan. It is becoming highly important to pay attention to preventive measures, because if we want to keep healthy teeth, we obviously must protect them from caries and so on. Fluoride is considered a key player in this scenario, but we believe there’s also a major role for Medical Hydroxyapatite. That’s what’s in our products, and we believe it will continue to make their sales grow.

Roslyn: It’s all about mineral replacement. As you said, salivary flow weakens as you get older. Just by using it every day, our product supplements the mineral provided by saliva and supports the natural healing process. We’ve tried to apply that idea to everything we do; one of our mottos is “Helping nature help you - supporting natural recovery processes,” and that’s part of the philosophy behind our toothpaste as well. We’re supporting what nature’s already doing.

As Shuji said, suddenly in Japan the population is getting older, and people are keeping their teeth for much longer now. That’s likely to become a worldwide trend, so mineral replacement is all the more important to achieve that.

One of our new developments is a technology called Powder Jet Deposition (PJD), which has just been submitted for regulatory approval. It’s a medical device that the dentist will use to spray onto your teeth a new coating of hydroxyapatite. It’s a technology that shows great promise, because it will strengthen teeth, especially children’s, to protect them from decay. Currently dentists use sealants or resin coatings to prevent caries from starting, but those materials are foreign to the teeth, they block remineralisation, and there can be leakage, so secondary caries can still occur. But since tooth enamel is already 97% hydroxyapatite, with this new technology you will simply add an extra layer and remineralisation will be able to continue. We see this as something that has great future promise.

Another exciting application will be tooth whitening. This is usually done by abrasion or bleaching – which are not good for your teeth and can also cause hypersensitivity. In this case, because tooth enamel is basically semi-transparent, and tooth whiteness comes from the color of the ivory beneath, if you just coat the tooth with more hydroxyapatite, it will still be semi-transparent. However, if you put a tiny portion of pigment into the hydroxyapatite, you can adjust the colour of the teeth as well. This is something we’re very much looking forward to in the future. You’ll be able to choose your colour, have a new layer of hydroxyapatite sprayed onto your teeth, it will be totally painless, and it won’t come off; it’s a permanent solution that will whiten and strengthen your teeth at the same time.

You have other product lines such as your anti-bacterial agents, health drinks, and cosmetics for example. Could you tell us more about these non-oral care health products you’ve launched, and which are you looking to strengthen sales in?

Roslyn: We’re perceived as a toothpaste company, but we prefer to be referred to as a “hydroxyapatite company.” We’ve specialised in hydroxyapatite in a number of areas in which we want to develop further. Some haven’t reached the product stage yet, but, for example, we are also pioneers in the use of hydroxyapatite as a catalyst for producing fuels such as bio-butanol. We’ve worked with companies like DuPont and others to bring that technology to the market, but have had to face competition from factors such as declining oil prices, the emergence of shale gas on world markets, and bio-fermentation processes, while our critical raw material, bioethanol, suddenly became wildly expensive as supply couldn’t keep up with the demand for it, for new uses such as bioplastics etc.

Sakuma: The point about bioethanol was that we could use it to generate fuels that are plant-based rather than fossil-derived. That’s because the refuse from plants like sugarcane or corn is used to generate the bioethanol, and we could then use it with our catalysts to produce higher order carbon compounds like butanol and so on.

Roslyn: We don’t produce the raw material - our contribution is the catalyst you use to convert the bioethanol to higher value-added fuels. Shuji could even drive around on a motorbike using the fuel we generate.

Sakuma: The catalyst project was my idea initially, because there was a time when it was really cheap to purchase bioethanol from countries like Brazil. It was about ten to fifteen Japanese yen a liter around the turn of the century. But it soon became dramatically higher, more than four or five times that.

I thought it was especially meaningful in terms of social contribution. If we could produce biogasoline for around thirty yen a liter, then even though it would give off carbon dioxide (CO2) when used, the carbon dioxide would be absorbed by plants, and the plants used to produce more bioethanol, resulting in a new kind of fuel cycle completely different from reliance on fossil fuels. That was one of the main goals we were targeting, because we wanted to contribute to a reduction in global warming in that sense.

Roslyn: We have a lot of patents in that area, which is why we managed to work with international chemical companies. But it’s the sort of project that is highly difficult to develop and run, and it competes with other approaches such as using bacteria to produce biofuels. Ours is a system of classical chemical catalysis, but using pure hydroxyapatite, which was originally used only as a substrate for other catalysts. Shuji insisted on using just hydroxyapatite, which was a major breakthrough. We discovered it works well, and that’s another example of how his basic intuition was correct.

As regards anti-bacterial agents, most products are organic, and can lead to discoloration of the materials they are used in, and can lose their effectiveness over time. But ours are totally inorganic and they don’t cause discoloration, and seem to have a longer effect.

Another feature of hydroxyapatite, used in chromatography and other applications, is its strong affinity for protein. One example is the way it collects bacteria in the mouth when you’re brushing your teeth. Hydroxyapatite doesn’t kill the bacteria, but it helps gather and clear them away when you rinse out. And ironically it has a stronger attraction for bacteria that cause tooth decay. That’s because teeth are made of hydroxyapatite and that’s where cariogenic bacteria naturally settle and form plaque. For some bacteria, it’s the only place where they can replicate. So when you brush your teeth, these bacteria and bacterial fragments tend to adhere to the hydroxyapatite particles and can be expelled from the mouth, which helps improve the balance of the oral flora over time. This is a benefit of using this mineral.

This same function of selective adherence is what we’re using in our skincare products. We developed a specific type of hydroxyapatite which we found would pick up and remove certain excess and oxidized skin oils, as well as dead skin cells and so on, while tending to leave some of the oils you need for lubricating your skin. This is the main point of the skincare line-up we’ve developed. It took a number of years to get everything in place, but now we really want to see this business progress. Skincare is a fiercely competitive market to break into, but we’re in it for the long haul, and we plan to make every possible effort to succeed.

As Shuji mentioned, we are also developing medical devices, and the first one, recently approved, is a cream for treating dentinal hypersensitivity, called Apashield. We have a dental route partner who will be handling the product, and it’s now in the early pre-marketing stage. We recently did a trial, offering samples to dentists. But the company arranging it had a problem with their website, and instead of offering around 100 sets, they didn’t stop the applications till there were over 400. We struggled and somehow met the demand, and we received an excellent response from dentists who tested the product. At least 68% said it worked well, although in some cases two applications were required.

The way the product functions is by filling and sealing exposed dentinal tubules. Exposure usually occurs when the gums recede, or excessive brushing weakens the surface enamel, so that stimuli such as heat and cold can gain access to the tooth nerve via the fluid in the exposed tubules. We believe this is going to be a really successful product.

You’ve had a subsidiary in Munich since 2017 and you’re currently exporting to twenty different countries. What new countries are you looking to approach? Would you be interested in doing it through new sales offices, joint ventures, or M&A?

Roslyn: We didn’t really intend to export, but we were being constantly approached by people wanting to buy from us. Our export business has basically been responding to people coming to us. In the case of Germany, we went into the EU because we had begun setting up partnerships with companies wanting to buy our products, and we realized that we needed to have a European base. Even though the regulatory system is not like the FDA or Japan’s, you need to be based there. That’s the reason why our subsidiary was put in place.

Up until then we had responded to partnership requests. So Germany is the only country where we’ve gone in ourselves and tried to get into the market – and we’re finding it hard. People ask us, why are you trying to get into Germany? It’s a notoriously complicated market with a very different distribution system from what we’re used to here in Japan. So this is quite a challenge for us. On the other hand, we’re learning so much from being there. As a logistical base for the other countries we supply, it was a great move forward, and it’s also a great experience for us to have to go in and sell our own product ourselves. Up till now, in all other markets, it has been our partners who do the marketing and they’re doing a marvellous job.

We still have pending approaches, for example from Eastern Europe, and various things in the pipeline, but it’s mostly people coming to us, which is exciting for us. Nonetheless, it’s difficult with COVID-19. We’ve had to cancel trade show participation, for example. But that’s about the extent of the marketing we’ve done overseas; we’ve gone to academic meetings and presented our research, and occasionally exhibited at them, and we’ve been to the major world dental show in Germany a couple of times. Just by being there, we’ve attracted attention. People come to us, and that’s how it starts.

A feature of Sangi is that we don’t produce our own products, manufacturing is subcontracted. That was part of Shuji’s philosophy; he just likes to develop products, that’s the fun part. In the beginning, we didn’t even sell them ourselves, though we do have a sales team now; we had other people selling and manufacturing. That has given us the freedom to concentrate on product development.

As for expansion overseas, we’re really acting in response to others, so it’s hard to say which country will be next. We would like to get into America, but that’s a very special case, and we’d like to do it on our own terms.

Sakuma: As Roslyn highlighted, hydroxyapatite toothpastes have really taken off in Europe, and we’ve counted more than 50 brands in Western Europe alone. Quite a number either emulate Sangi’s claims or designs, or quote Sangi’s research. We’re honoured because from our position, we see European countries as highly developed, and it’s great that companies are now building on the technology we developed decades ago. Because of a serious challenge to our initial brand registration by Colgate, over a number of years, and because we needed to provide regulatory reassurance concerning the safety of our nano-ingredient, Sangi entered the European market relatively late. But the response from consumers and dentists alike has been good, and we’re confident that we’ll develop a firm niche for our pioneering products there.

Looking to the future, when you step down and pass on the company to the next generation, if we were to come back and visit you again on that very last day, what would you like to have achieved by then?

Sakuma: Hydroxyapatite is a material with unlimited possibilities. At the very least, I would like to have expanded it to other applications such catalysts and medical devices, and to have built a firm market in those new fields. It seems too limited to see it restricted to a market solely for toothpaste products.

Roslyn: We’re often asked what size we want to be in terms of sales. Shuji sometimes spouts huge numbers, but I never think in those terms; I’ve always believed that results will naturally follow if you’re doing what you’re good at, putting every effort into it, and enjoying yourself while doing so. Because we have so many things in the planning stages, one of the things that Shuji and I would of course like to see is how they develop and come to fruition.

One thing I’d like to stress is that Sangi really tries hard to come up with things no-one has done before. If somebody else starts with what we’re thinking of doing, we may drop out, because we don’t want to be seen as imitating anyone. At one point in our PJD project – which involves mechanical equipment as well as hydroxyapatite – we needed a partner to work with us on the mechanical part. We approached one of the largest Japanese dental equipment manufacturers, and were amazed when they said, “We don’t work on original products. We focus on improving things that already exist.” They weren’t prepared to take the risk of developing an entirely new product. We then approached a European company, and their response was similar. They said it was a great idea, but it probably wouldn’t sell.

It’s an issue we face in quite a few areas; the more original your idea, the longer it takes and the harder it is to get it accepted, and in particular, to get it through the regulatory system. It’s definitely a lot easier when there’s a precedent and it’s just another version of something that already exists.

One example is a product we have on the market in Japan called APAGARD Deep Care. It’s a remineralizing dental lotion, and the concept is to use it after toothbrushing, just as you use conditioner after shampooing your hair. But it’s new – there’s no category for that in Japan. So the only way to get it registered was as a liquid toothpaste. That allows us to make claims of anti-caries and remineralisation, but because it’s classified as a “toothpaste,” by law we have to show a picture of a toothbrush and include brushing instructions, which isn’t appropriate for this product at all. In Europe, thankfully, we can sell it as a lotion, but not in Japan. This is all the more disappointing, because we have a clinical study just published, showing that using the lotion after toothbrushing increases remineralization significantly. It’s also beneficial for people suffering from “dry mouth,” i.e. inadequate saliva flow. But again, we can’t say that yet in Japan.

0 COMMENTS